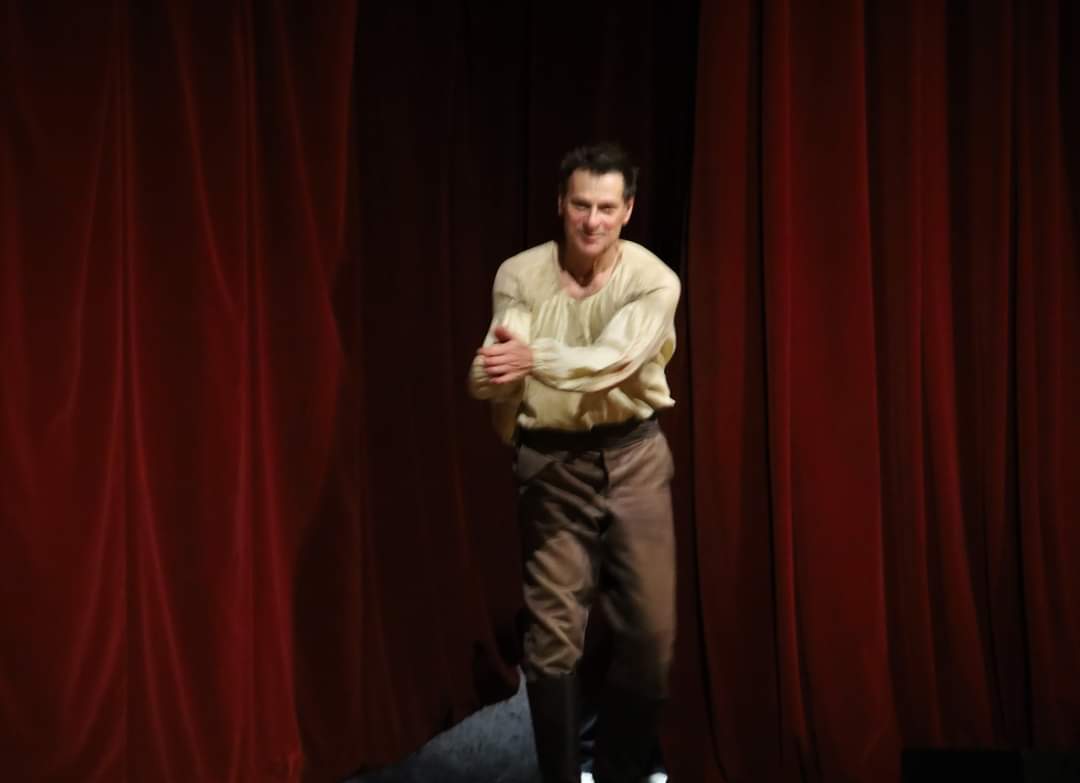

Photo: Angelo Capodilupo

A new interview with Simon has been published by the Vienna State Opera in the October 2022 edition of their ‘Opernring Zwei’ magazine.

Once a KING, Another Time a COURT JESTER

On stage, Simon Keenlyside creates, both vocally and dramatically, images of people of incredible vitality. He makes the characters he portrays believable by highly intelligent psychological insight, a rich variety of facets, a mastery of nuances as well as a dedication that infects his colleagues – all this made him one of the finest and most important interpreters of his Fach. His popularity is accordingly great among the audience of the Vienna State Opera. In 2017 the British baritone was awarded the title “Österreichischer Kammersänger”, which was, so to speak, the documented form of the enthusiasm that the auditorium meets him with every evening in this house.

Now he is returning with two important roles in the Verdi repertoire: as Rigoletto in October and as Macbeth in November.

As much as the public in general is inclined to feel sorry for Rigoletto, there is as little sympathy there for Macbeth. Why is that? When his appetite for revenge becomes clear, at the latest, the court jester has little that makes him likeable, and when Macbeth at the end, burning inwardly, faces his downfall, something like compassion should stir up.

SIMON KEENLYSIDE Because the narratives each trigger very different dynamics. Let’s examine the two figures separately: Rigoletto’s entire striving is for his daughter Gilda. The desperate attempt to protect one’s own child will meet with deepest understanding not only from fathers and mothers in the auditorium. His beloved wife has died, he is a single parent – this is no easy fate even today, much less so in former times. In addition, he has to operate in an environment that is hell for him – at the mercy of the powerful, deformed, despised by everyone. That also makes Rigoletto vulnerable. The fact that, driven by his social impotence, he moves towards revenge is perhaps to be condemned from our present point of view. But even 100, 150 years ago, there were other parameters that ultimately exculpate him. And Macbeth? Excessive ambition is repulsive in itself, but if, in addition, someone is out to murder children, they have lost every spark of sympathy forever. Besides, he doesn’t seem too intelligent, a compliant tool in the hands of his wife – no particularly engaging traits.

But the protection Rigoletto grants Gilda is rather questionable. Ultimately, he locks her up, prevents her from living, from unfolding her self.

SK First of all, he knows the Duke’s court and environment, so he knows what can happen to her, and how great the danger is that she will get into this vortex. And then. . . there are very different forms of love that are intentionally right, but go in the wrong direction. I know a farmer in Wales whose love for his children is obvious and unambiguous – yet he is excessively harsh and hard towards them. Shaped by his upbringing, his imagination, he thinks he’s doing exactly the right thing.

In many countries of the global South, for example, there is child labour with the knowledge of the parents. But if you asked them whether they loved their children, they would answer with a clear “yes”, out of real conviction. It is the terrible social circumstances that force them to commit these crimes. And in Rigoletto’s case, it is social constraints, various personal traumas that make him act in this way. His feelings of love are true, but he doesn’t know how to put them into practice. And so he makes mistakes. And the worst thing is, of course, that his revenge plan goes wrong and Gilda is murdered.

Macbeth may have been driven by trauma, too. By the trauma of childlessness.

SK I don’t think so. Until he kind of mutates into a villain, there’s not a single hint that he cares about children. And the idea of founding a dynasty doesn’t matter anyway at the beginning. He is a soldier, his life is war and the victory to be won. This is his world, this is what he was trained for. And his intelligent, terrible wife uses it for her own ends.

Does she love him?

SK I think she loved him. On the other hand, like other marriages of past centuries, especially among potentates, the marriage between Macbeth and his wife was probably an arranged relationship, in which power and possession were at stake, not affection. Ultimately, however, it is insignificant, a possible love is not the subject of this story.

Is Rigoletto an Italian Wozzeck?

SK Difficult question. There seem to be some analogies between the two figures and fates. But in the end, I would say “no” to that question. Because a fundamental difference is quite obvious: In “Wozzeck”, Berg shows us a person who is basically shattered by the fact that his purpose in life has been taken away. He had a function as a breadwinner for his family that kept him going to some extent in his desolate life. Through Marie’s infidelity, the painstakingly constructed and maintained life plan collapses. Verdi, on the other hand, tells us another story. Rigoletto is not shattered after Gilda has lost her honour in his understanding, but rather rebels against the system. He doesn't break down until Gilda dies, but her death is only partly his fault.

Both Verdi and Mozart have created immensely complex characters, and put them on stage without judging them. But what is the difference in the approach of the two composers?

SK Especially the three Da Ponte operas were created in close temporal relation to the French Revolution, so ideas such as human rights, freedom and responsibility always play a major role in Mozart’s work, at least subliminally. In all of his characters and the relationships shown, general human conflicts, mistakes, strengths, peculiarities are thematized. Verdi, on the other hand, always wonders how very specific people in very specific situations get along with the world. In other words, Verdi focuses on a very concrete individual with all their distortions.

To what extent is Verdi’s Macbeth the Macbeth of Shakespeare?

SK During rehearsals for the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, the famous choreographer and director John Cranko once warned a singer not to want to show too many different things at the same time. Whoever on stage addresses four or five messages to the audience at once, Cranko says, won't get across a single one. This is profound wisdom. When applied to the works for the opera stage, this means: the more complex the composition, the less complex the libretto may be. Otherwise you can’t see the forest for all the trees. The great thing about Shakespeare’s works are not the stories themselves, but what is expressed in each line and how it is expressed. Even a Boito in Otello and Falstaff does not reach this high literary level, let alone Verdi's other librettists. And that’s a good thing. Verdi’s compositions would not bear the density of Shakespeare’s language at all, it would result in exactly that “too much” Cranko meant. Seen this way, Verdi’s Macbeth is not the Macbeth of Shakespeare. Verdi’s Macbeth is by Verdi.

Link to original article in German